In the past decade, a number of anthropologists have provided fascinating insights into people’s digital behaviour. People have been increasingly using the internet for a varied number of reasons such as to socialize, consume and produce knowledge, for entertainment, work etc. Moreover, the pandemic further accelerated our usage of the digital. Even in India, as the internet and smartphones become more accessible, we are noticing a huge jump in the number of people using the internet and connecting digitally.

The “next billion users”, a term that “describes the internet opportunity in emerging markets” – was first coined at Google’s mountain view headquarters in 2015 and sheds light on the growing significance of such a phenomenon (Mitter). Moreover, an article in the Economic Times, stated that “Indian consumers are now viewing videos online for an average of 5 hours and 15 minutes everyday, amongst the highest in the world” (Sangani).

Thus, as we are increasingly spending more time in the online world, it becomes imperative to understand it deeply. Moreover, the growing demand to understand this space can also be attributed to the growth of fields such as digital anthropology; a sub branch of anthropology that focuses upon understanding people’s digital behaviour. Many anthropologists have conducted ethnographic research questioning a number of previously held assumptions regarding people’s online and physical world behaviour. Several such arguments have increasingly gained acceptance from academia in general. However, I rarely notice these learnings being incorporated in non-academic research. As researchers we strive to better understand our consumers and are constantly trying to go beyond the obvious. Researchers exploring consumer behaviour acknowledge the growing influence of digital on the lives of the consumers. Further, they also acknowledge that the young consumers are socializing, learning, shopping, and consuming through digital mediums. Despite this, while conducting research we hardly ever try to approach a consumer’s life in a way that we would be able to capture such intricacies.

While designing a research, we often approach the online and offline as binaries. Thus, most of the time researchers explore the digital behavior independent of the physical behaviour. What this means is that, when a person is interacting with the digital they are not a part of the offline or when a person is in an offline/physical moment they are not connected through the digital. We hardly ever try to approach a consumer’s life in a way that we acknowledge these new emerging complexities where a person is simultaneously in both these worlds.. In non-academic research, we hardly ever design research that allows an opportunity to capture these new complex realities of the consumer’s life.

In the following blog, I share a few learnings that should be incorporated at the research design stage so that we can develop a more contemporary understanding of our consumer.

1. The online and offline worlds are not mutually exclusive

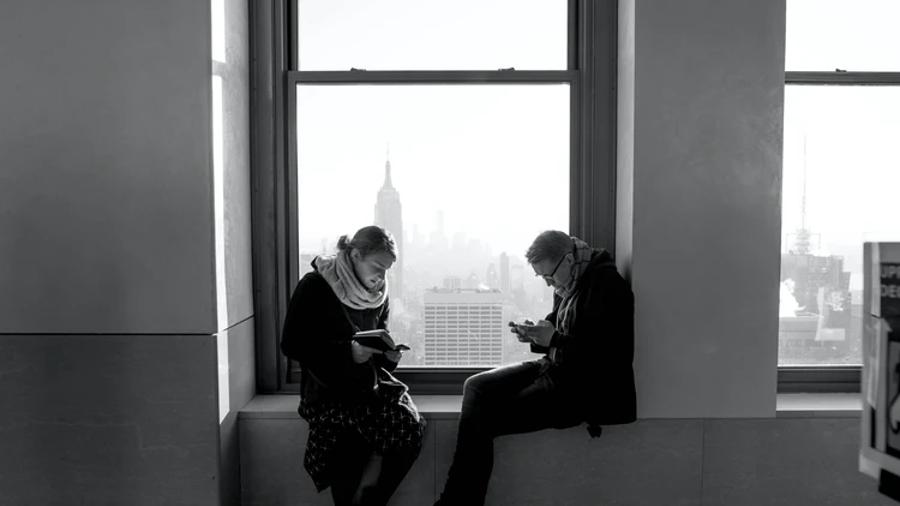

Throughout the day, people are simultaneously engaging in both the online and physical world. This often makes it hard to say with certainty when a person is in the online or offline world. Let’s understand this further through some examples:

1. A group of friends are sitting together at a restaurant and are constantly on their phone every few minutes. They could be engaging with friends/family through Instagram/WhatsApp/Facebook/Snapchat, etc. They click pictures of themselves, food, restaurant’s decor and are uploading these in real time through ‘stories’ or ‘posts’ on any of these platforms. So, even when they are physically together sharing a meal, they are also connecting with people (the same friends physically present or people across the globe) digitally.

In such a scenario, do we consider them to be a part of the physical/offline world where they are consuming a meal together? Or can we claim that since they are all connecting with others through different digital platforms, they are actively present in the online world while only physically inhabiting a space in the physical world?

2. In the Delhi metro, one can often observe people reading, watching a show/movie, listening to music or even playing a game on their mobile phone. Though the metro appears really crowded and people are close together, we often observe them disconnected from their physical space and lost in their devices. In such a setting, do we consider these people to be together in the offline world because they are physically present in the metro or do we consider them to be in the online/digital worlds as they are not interacting with the physical space or the people around them?

By highlighting such mundane moments, I want to emphasize how regularly people navigate between the online and offline worlds throughout the day. In the book “How the world changed social media” , the authors argue that “we reject a notion of the virtual that separates online spaces as a different world. We view social media as integral to everyday life in the same way that we now understand the space of the telephone conversation as part of offline life and not as a separate sphere” (Miller et al. x).

Thus, research designs need to incorporate ways that allow researchers a means to understand such new ways of being, where most consumers are online/offline at the same time.

2. Online is no less real than the offline

Until recent times, it was common to read or hear remarks claiming that the online/digital was less significant than the physical world. We were, after all, living in the physical world and thus it was our interactions and relationships in the offline/physical world that were deemed more significant. There was a common assumption underlying such claims that our interaction in the digital space was somehow less real and thus, less important to understand.

However, creating a hierarchy where we place one experience above the other, which is primarily a result of our own narrowmindedness, is an overly simplistic approach to have. Instead, I argue that we need to look at how the “virtual world can act as “another platform for the human operating system. They do however, transform what being human can mean, recalling how “we have used our relationships with technology to reflect on the human” (Turkle 1995:24). Thus, instead of pitting one against the other, and only understanding the online from the lens of the offline. We need to acknowledge that “alongside continuity there is change. In the age of Techne, human craft can – for the first time – create new worlds for human sociality”(238).

However, many research studies done on social media, multi-player gaming worlds showcase that many players often feel more ‘real’ or closer to their real self in the online world. For instance, Yasmin Kafai and Deborah Fields in the book “Connected Play”, largely explore the interactions of kids within virtual worlds and how these affect their physical worlds. In their work, they highlight that “anonymity and invisibility of physical bodies allowed youth in their study, especially girls, to be freer in what they said and to whom they said it” (Kafai and Fields 58).

In the book “How the world changed social media”, the authors highlight that, “when the study of the internet began people commonly talked about two worlds; the virtual and the real. By now it is very evident that there is no such distinction – the online is just as real as the offline” (Miller et al. x) Thus, it becomes imperative to acknowledge that we can no longer dismiss the ‘online’ worlds as less significant than the ‘physical’ world. They have brought to the forefront the need to independently study the online/digital worlds as a way to understand people.

3. Online behaviour is as diverse as offline behaviour

Until recently, one often observed that “most studies of the internet and social media are based on research methods that assume we generalize across different groups” (Miller et al. v ) However, Daniel Miller and his colleagues, highlight that a researcher exploring a particular digital platform needs to contextualize it within the culture (locate it in the offline/physical culture).

Let’s explore this in some depth.

For instance, a study exploring how people interact on Facebook cannot simply be a study on Facebook. It will have to understand what Facebook means in that specific geographical location. Researchers will have to seek answers to their questions within that culture.

Questions such as:

1. Why do people use Facebook?

2. What do they generally do on Facebook?

3. When do they use Facebook?

Will have a unique meaning within that geographical location. The interactions on Facebook will have to be located in the culture that is being studied. What I wish to highlight here is that “the point illuminated by the anthropological approach is that Facebook only ever exists with respect to specific populations; the usage by any one social group is no more authentic than any other” (Miller et al. 15).

Lets explore this further through another example:

In India, Twitter is mainly used to make announcements, share news or provide updates on things that are deemed important at a societal level. Twitter is largely considered a formal platform where we talk about things that are relevant to the society as a whole. Celebrities, political leaders, academicians and others of similar stature generally use the platform to share their opinions on current, trending topics or might share some personal/professional news with their followers.In India, it’s a platform to broadcast information.

Amongst all the social media platforms, Twitter is the least popular with the masses here. “The Indian user base for Twitter totals around 26.7 million, a far cry from the other social networks.” (Mihindukulasuriya) To understand this a little more, the reporters at The Print had asked a few students regarding their usage of Twitter. Here are a few consumer verbatims from the article that can shed some light on how people understand Twitter:

“I’m used to reading links on Facebook… even what people say on Twitter” (Student 1)

“I thought Twitter is for celebrities… so I don’t use it.” (Student 2)

“I use Twitter sometimes… for updates.” (Student 3)

(Mihindukulasuriya)

One thus realizes that Twitter for various reasons is not extremely popular with the masses in India. Moreover, there is often so much trolling that happens on Twitter that it has led to public figures even deleting their accounts temporarily from time to time. However, Twitter is understood and used in a variety of different ways across the globe. For instance, in Japan Twitter is extremely popular and people use it “more to socialize than to broadcast news” (Beck). For a number of reasons that I won’t go into detail here, a lot of research has highlighted that Japanese people find a lot more appeal in Twitter than Facebook and the reasons are quite culturally rooted.

What becomes evident through the above example is that a digital platform could hold very different meanings in different cities across the globe. Thus any digital platform cannot be generically given a single meaning. What I wish to emphasize here is that the social media or by extension the digital is not a standard static space that can be studied without the context of the offline/physical. Rather, what the authors highlight through their several books is what “social media has become in each place and the local consequences, including local evaluations” (Miller et al. v).

Each of the three learnings, if incorporated in the research design, can allow us to better capture the complex realities of our consumers.

References

- Sangani, Priyanka. “Indians Watch the Most Online Video Content per Day: Survey.” The Economic Times, 24 June 2020, economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/media/entertainment/indians-watch-the-most-online-video-content-per-day-survey/articleshow/76552181.cms?from=mdr.

- Mitter, Sohini. “With Half a Billion Active Users, Indian Internet Is More Rural, Local, Mobile-First than Ever.” YourStory.Com, 5 Mar. 2021, yourstory.com/2020/05/half-billion-active-users-indian-internet-rural-local-mobile-first/amp.

- Beck, Taylor. “Why The Japanese Love Twitter But Not Facebook.” Fast Company, 29 Aug. 2013, www.fastcompany.com/3016498/why-the-japanese-love-twitter-but-not-facebook.

- Miller, Daniel, et al. How the World Changed Social Media. UCL Press, 2016.

- Kafai, Yasmin, et al. Connected Play: Tweens in a Virtual World (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning). Illustrated, The MIT Press, 2013.

- Mihindukulasuriya, Regina. “Why Young Indians Aren’t on Twitter.” ThePrint, 13 Nov. 2018, theprint.in/features/why-young-indians-arent-on-twitter/148907.

About the author

Rupali Kapoor works as the Research Officer for the Consumer Culture Lab at IIM Udaipur. She is trained in social and cultural anthropology from UCL. She is interested in decoding our everyday interactions with spaces, objects and fellow beings.