Beauty is an important concept in Indian consumerism, making India one of the biggest markets for beauty products in the world. Within the Indian beauty market, one of the highest selling products are skin fairness creams. The notion of beauty is heavily influenced by culture. Fair skin is synonymous to the Indian notion of beauty. In this article, I briefly analyze the cultural meanings associated with skin whitening in India, highlighting gender differences in these meaning systems. While beauty is desirable to both genders, we observe differences in the role beauty plays in identity projects of men vs. women. Through this exercise, I aim to elucidate some deep-rooted mental models that unconsciously inform judgements about skin color in the Indian society, and how these judgements differ by gender.

Unlike the west, Indian differences in skin color do not connect with racism (all Indians belong to the same sub-continental race). Skin fairness in India lies in the domain of “colorism”—different tones of the skin within the same race. If we dismantle the subject matter of colorism, it boils down to the difference in the tone of skin color—dark vs. light. What meanings do these two tones carry in our minds? To understand the different trajectories of meaning, we need to understand how color moves on the continuum of darkness and lightness. The continuum can be understood by applying two concepts of color theory—shade and tint.

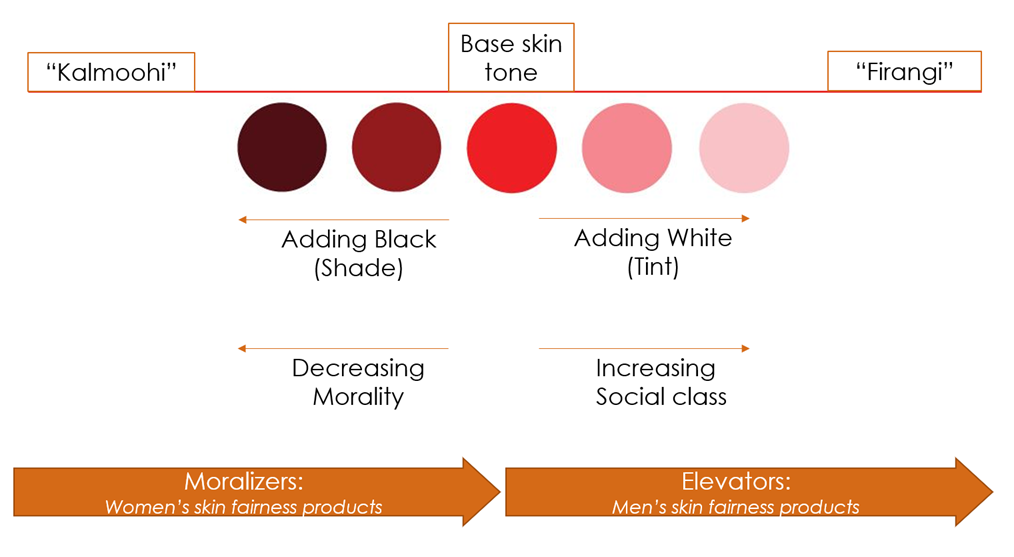

As it can be seen in the image above, there is a base hue which can be transformed into a lighter or darker version by adding white or adding black to it. We can assume that in a culture, there is a default skin tone and the relatively “fairer” and “darker” tones would be seen as tints and shades respectively. I propose that there are two parallel axes at play in Indian skin culture: (1) the shade axis, and (2) the tint axis. The addition or removal of blackness falls in the realm of shade—the axis of morality. The addition or removal of whiteness falls in the realm of tint— the axis of social class.

Cultural meanings are embedded in products through meaning systems created in advertising and packaging (McCracken 1986). To understand the cultural meanings of skin whitening products in India, I decode some print advertisements and packaging designs of skin fairness products available. This method of semiotic analysis attempts to pick up ‘signs’ from brand communications and decode underlying meaning systems. On analysing advertisements of skin fairness products for women vs. men, we can roughly map the two axes (i.e. shade and tint) to each gender. We can see that skin fairness for women is playing in the shade-space of morality. For women, fairness products are predominantly moralizers that are removing “blackness”—navigating away from being a potential “kalmoohi”. Whereas, when we look at skin fairness products for men, we are playing in the tint-space of social status. For men, fairness products are elevators that are adding “whiteness”—navigating towards the “firangi” colonial master.

Moralizing the Kalmoohi

Skin whitening for women: Moral beauty shaped by the marriage market

The cultural concept of “kalmoohi” is important to discuss here. Kalmoohi is a derogatory Hindi word that literally translates to “a woman with a black face”. This word is usually used to refer to a woman who has done an immoral act (for example, a pre-marital affair that has historically been designated as immoral in India). Interestingly, there is no equivalent word related to skin color to derogate a man who has done an immoral act. When a woman has a black face, she is immoral. But to perform well in the marriage market (or in the Indian job market if you are a woman), you need to whiten your face. Skin-whitening products for women, hence, play the role of moralizers—helping you to navigate from being a potential kalmoohi to a moral woman.

The notion of feminine beauty in India is deeply influenced by the marriage market code. In fact, the genesis of skin whitening products through the launch of Fair & Lovely—was inspired by matrimonial ads that frequently asked for “fair” brides. Although we see the emergence of love-marriages, arranged marriages have been the dominant form of marriage in India. Match-making is done on the basis of the bride’s family history, and the physical appearance of the bride (see our curated content on the revealing Netflix series on Indian Matchmaking here). Unlike love marriages, the boy and the girl do not get the opportunity to evaluate each other in terms of personality and character traits. What attributes are most important while making a choice in the marriage market? While for men, the attributes are related to career and wealth, for women, the desirable traits are related to beauty and morality.

Due to the patriarchal setup, it is not about the boy entering the girl’s family, but it is about the girl entering the boy’s family. The girl, who is an outsider, is welcomed and embedded into the web of the boy’s family. Here, we need to note an interesting phenomenon of ‘web of shared contagion’. In India, it is generally believed that people “are linked together along blood lines in a web of shared bodily fluid, such that pollution incurred by one person spreads to close family members, just as a snakebite in the leg quickly spreads throughout the body.” (Appadurai, 1981; Marriot, 1976). Pollution or contamination by one member of the family is believed to contaminate the honour of the entire family. Hence, many issues of physical hygiene (and physical perfection or beauty) that are considered as personal issues in western cultures, are seen as moral issues in India (Shweder, Mahapatra, & Miller, 1987). It is interesting to note that this moral contagion is believed to occur only through women’s bodies and not through men’s bodies. When the girl enters the boy’s family through marriage, the groom’s family faces a risky trade-off of the girl either bringing in luck (the notion of “ghar-ki-lakshmi”) or contamination (the notion of “kalmoohi”) into their family. For women, skin color places them in the hierarchy of caste, an important parameter to evaluate her family and upbringing in the marriage market. The cultural meaning of women’s beauty has a lot of its roots in the caste system. Bollywood movies repeatedly depict the upper caste girl as fair and the lower caste girl as dark. Skin fairness, hence, becomes a yardstick to evaluate the girl’s genealogy.

But how is skin fairness related to morality? To explain this, let me introduce you to conceptual metaphors. Lakoff and Johnson, in their book, Metaphors We Live By, discuss a powerful concept of experiential metaphors where people’s notions of abstract concepts such as power, love, and morality are mapped to physical experiences such as height, temperature, and physical cleanliness. For example, the metaphoric link between physical dirt and moral impurity induces people to wash their hands (or take a dip in the Ganges river!) to wash-off their sins. When skin fairness operates in the “shade” axis, it is the presence or absence of “blackness” that makes a difference. Blackness is metaphorically connected to the concept of dirt and immorality. Dark-skinned Hindu gods are usually visualized with blue skin in paintings. Negative characters are visualized with dark skin in children’s comic books. The notions of dark times, black market, blackmail, blacklist, blackspot, muh-kaala (blackening of face) imply that black has an immoral character.

If we look at the earliest advertisements of fairness products for women, we see signs of products framed as “moralizers”. These are divine interventions (magical rays of light) from gods in the form of a sacred blessing or boon. The metaphor strongly links to the ethical cleansing process associated with taking a dip in the sacred Ganges river.

The words such as “flawless”, “a gift from the gods” and “miracle” signify divine cleansing

Divine rays entering the woman’s face, like a moralizing force (boon or vardaan)

Pink fairness and its equation with innocence (kinderschema) is adding to the moralizing force

Elevating to a Firangi

Skin whitening for men: A sign of colonial power

While fairness creams were predominantly women’s beauty products, over the last decade we see growth of men’s fairness products in India. Men are seeking skin fairness, not as morality signals, but as sources of power residing in status symbols. A daily wage labourer who toils under the sun is likely to have dark skin, whereas, an elite businessman who spends his entire day in an air-conditioned room is likely to sport fair skin (as can be seen in the advertisement below).

Transforming the daily laborer into an elite businessman

If we look back at our colonial history, Indian masculinity was threatened by the suppressive powers of colonial rulers. The colonial discourse of the effeminate Indian male lacking in Victorian masculine virtues turned the Indian male into a pejorative self-image. The colonialists had selectively labelled male bodies as laughably feminine or brutally savage-like (Alter, 2000). Colonized bodies were subjugated. Colonized skin was darker than the colonizer skin. The colonizer skin had more whiteness, and hence, more power. The white-skinned British rulers—known as “firangi” (translated as “foreigner”)—have been associated with greater power and social status. Having a fair-skinned male child in India, one is likely to receive comments such as, “Your child looks like a foreigner”. These comments are made as compliments categorizing the child into a superior social class.

The words “jewel in the crown” allude to reclaiming one’s political position of power.

The words “PowerWhite” connote white as a source of power (for men)

As it can be seen in the advertisement above, the repeated usage of the word “more” shows that men’s fairness is working in the additive space. Products are elevators that are helping men rise above in status and power by adding “more” whiteness—the tint process. Whereas, women’s fairness is working in the preventive or subtractive space. For women, it is about removing “flaws” (with repeated usage of words such as flawless). Products are moralizers that are helping women cleanse away the “blackness”—the shade process. We also observe some ads for women’s fairness creams that show girls achieve career progression after their skin gets fairer. So, the gender distinction is not watertight in the additive space.

Unilever recently changed the name of their skin lightening product from “Fair & Lovely” to “Glow & Lovely”. While the motive behind this move is noble enough to start a conversation about being comfortable in one’s skin, does it help move the trajectory of the product out of the “moralizer” space?

References:

Alter, J. S. (2000). Subaltern bodies and nationalist physiques: Gama the great and the heroics of Indian wrestling. Body & society, 6(2), 45-72.

Appadurai, A. (1981). Gastro‐politics in Hindu South Asia. American ethnologist, 8(3), 494-511.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago press.

Marriott, M. (1976). Hindu transactions: Diversity with-out dualism. Transaction and Meaning: directions in the anthropology of exchange and symbolic behaviour. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues.

McCracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of consumer research, 13(1), 71-84.

Shweder, R. A., Mahapatra, M., & Miller, J. G. (1987). Culture and moral development. The emergence of morality in young children, 1-83.

About the author

Dr. Tanvi Gupta is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at IIM Udaipur. Her research primarily explores the role of symbolic meanings in consumers’ lives, and how these meanings are shaped by culture and emotion.

Email: tanvi.gupta@iimu.ac.in

The views in this article are of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the institute.